We all have the same goal: safe, reliable, efficient, state-of-the-art vehicles accessible to everyone

Automated vehicles (AVs) have always inspired us to dream of the future. In 1939, a New York World’s Fair Exhibit entitled Futurama: Highways & Horizons enthralled visitors by showing a world of self-driving cars travelling on automated highways through futuristic cities. In more recent decades, automated vehicles have been used in many fields, with self-driving harvesters in agriculture, automated mining and construction equipment, and self-propelled torpedoes in military operations, to name a few. In a well-known contest in 2005, the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) funded a race through desert terrain, catalyzing the development of autonomous vehicles.

Today, we often take for granted some of the automation already in our vehicles to keep us safe, features such as electronic stability control (ESC), automatic braking, and collision avoidance systems. But what about a truly autonomous vehicle or a self-driving car?

Despite intense debates between those who want faster development and those who advocate more caution in testing and regulating autonomous vehicles, we all likely have the same ultimate goal in mind: safe, reliable, efficient, state-of-the-art vehicles which are accessible to everyone.

To this end, AVs are continuing to be built, tested and refined by diverse experts and organizations — auto manufacturers, universities, tech giants. And each employs different methods of development. Some rely more on machine learning while others rely more on computer programming. Some use LiDaR (Light Detection and Ranging) technology while others do not. Some are focused on building AVs for specific roads while others want AVs that can go anywhere. But no matter what the approach, safety must be the guiding principle.

What do AVs mean for safety?

It makes sense to work towards a world in which AVs help us get to our destinations more safely, efficiently, and equitably. AVs won’t ever get tired or sick or distracted. They will never drink too much alcohol and then drive. They will never have trouble seeing the road or other vehicles because of glare or darkness. They will never even run a red light or speed. In fact, they can react as soon as a risky situation is detected, often faster than a human. They could also be used constantly, rather than sitting idle, and always run at the most energy efficient mode. They could improve people’s health by providing mobility for those who are unable to drive, whatever the reason.

It also makes sense to think of AVs as part of the solution towards a world that is safer, cleaner, and more accessible for everyone. And, in fact, AVs are already a part of that solution with all the automated features that improve both our safety and our convenience (like self-parking features).

Levels of Automation

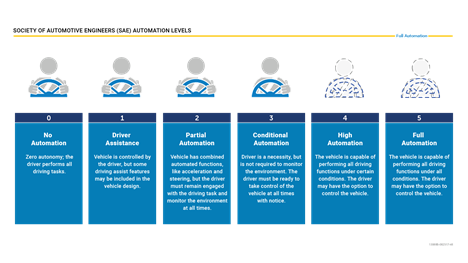

We sometimes hear the words automated vehicle or autonomous vehicle or self-driving car used interchangeably, but it’s important to remember there are levels of automation. The Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) has defined six levels of driver assistance technology from No Automation (SAE Level 0) to Full Autonomy (SAE Level 5). Currently, the highest level of automation on the market is Conditional Automation (Level 3), where the driver is still a necessity and must be ready to take control of the vehicle. Level 4 and 5 vehicles may be on the road, but only as test or experimental vehicles which still require a trained person behind the wheel, and they are not available for consumers to purchase.

Automation in Aviation

In 2020, the company Garmin Aviation won the National Aeronautic Association (NAA) Collier Trophy for “greatest achievement in aeronautics or astronautics in America” for its Garmin Autoland system. Despite the name, Autoland doesn’t refer to automobiles, but rather to an autonomous landing system for light aircraft. This system takes over if a pilot becomes disabled so that the light aircraft can land safely. Such an achievement in aviation might lead us to believe that a completely self-driving car is close at hand, but Garmin’s Autoland system is an emergency system which weighs the near certain catastrophe of no intervention against automated intervention to land a light aircraft. While there are many automated features in all types of aircraft, human pilots are still needed to fly airplanes. It isn’t surprising, then, that AV developers are still working hard to create autonomous vehicles for our roads.

Technology in Vehicle Automation

It is simply human nature to be more forgiving of other human beings for a mistake (such as a crash) and less likely to be forgiving of technology that has malfunctioned and caused death or injury. So, an AV must be cutting edge yet highly reliable. It must make an infinitesimally few number of errors. It must be much, much safer than a human driver. So the question remains: When will an AV that is safe be available for everyone?

Technology advances at exponential rates. As Gordon E. Moore, the founder of Intel, famously wrote, “the number of transistors that can be incorporated into one microchip will double every two years and the cost will be halved.” His Moore’s Law tells us that storage, networking, and other aspects of computing will continue to expand at amazing rates, which will enable better performance by AVs as well the road network on which they will be driven. This also means it would be difficult to predict when a safe vehicle without any human input will be available to the public, but most experts estimate that it is still quite a few years in the future.

Nonsense & the Swiss Cheese Model of Risk Management

The US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) has investigated several fatal crashes involving automated driving systems in recent years. The investigations found that an overreliance on automation combined with inattentive and/or distracted drivers were the “Probable Cause” of these crashes.

Access investigation reports:

https://www.ntsb.gov/investigations/AccidentReports/Reports/HAR1702.pdf

https://www.ntsb.gov/investigations/AccidentReports/Reports/HAR1903.pdf

https://www.ntsb.gov/investigations/AccidentReports/Reports/HAR2001.pdf

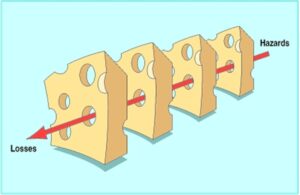

Even high-reliability organizations recognized for their exemplary safety culture, like nuclear power plants and air traffic control centers, always prepare for possible failures. They have layers and backups to protect themselves and surrounding communities. They use the Swiss Cheese model of risk management, developed by Professor James Reason, the world-renowned human factors scientist. The holes in the Swiss cheese are potential hazards or errors, but a loss (accident) only occurs if the holes all line up so that a hazard can get through. The more layers of protection we have (the slices of Swiss cheese), the less likely there will be a disaster because the hazard is less likely to get through. For AVs, an important layer of protection would be occupant protection (like airbags and seatbelts) and it would be foolish to remove that safety net.

Since AVs on the road today still need human input, the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) is working on ratings to help design safeguards for vehicles with partial automation to help drivers stay focused on driving and to prevent unsafe use of the technology. It’s hard to judge if a person’s mind is focused on driving, but technology can monitor your head posture, hand position, or gaze. If you stop behaving like someone who is actively engaged in driving, the system will alert you and, in cases of no response, even slow or stop the vehicle and call an emergency number. Having these safeguards is yet another layer of protection. This new IIHS program does not simply encourage safeguards that react to what the driver is doing, though. It also encourages automakers to design their systems to promote better communication and cooperation between the technology and the driver from the very beginning, which will promote safety by fostering a better understanding of technology and how best to use it.

Automated vehicles are, and will continue to be, an inspiring part of our reality. They allow us to imagine a world in which we all–no matter what our age or ability or where we live–can get where we need to go, safely and easily. As AVs continue to be developed in the coming years, it makes sense to do our part to stay informed. TIRF is doing its part with the launch of a new series of fact sheets examining a variety of automated vehicle issues and features. These fact sheets, developed in partnership with Desjardins, are freely available and can be easily integrated into a variety of learning strategies. There are also other organizations tackling this important issue such as Transport Canada and Partners for Automated Vehicle Education (PAVE). We can all play a part in ensuring that they are developed wisely and that we use them in the safest way possible so that AVs can fulfill their potential to increase equity, accessibility, and safety in transportation.

Remember, your brain is your vehicle’s most important safety feature.

Visit TIRF’s Brain on Board website to access the complete AV curriculum available in English and French.

Production of the AV Curriculum was made possible with sponsorship from Desjardins and technical expertise from Greg Overwater & Andrew McKinnon, Global Automakers of Canada.

#MySafeRoadHome blog co-authors: Bella Dinh-Zarr, TIRF Senior Advisor for Public Health and Transportation and Ward Vanlaar, TIRF COO, work collaboratively as co-authors. Bella trained in public health and injury prevention and is a former Vice Chair of the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), where she witnessed the importance of automation in aviation, rail, maritime, and highway safety. She loves all forms of transportation and is especially excited about the role that automated vehicles can play in improving mobility for people of different abilities and ages. Ward is a statistician and criminologist whose main fields of interest are traffic enforcement issues, risky driving behaviours, young and senior drivers, statistics and methodology, data management, safety performance indicators, and implementation of road safety programs. Loving both technology and driving, Ward is excited about the advancements happening today with AVs.

Related topics:

|

|

|

|

Source documents and resources:

https://www.nhtsa.gov/technology-innovation/automated-vehicles-safety

https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/history/museum-gordon-moore-law.html

https://www.iihs.org/news/detail/iihs-creates-safeguard-ratings-for-partial-automation

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1117770/

Washington State Department of Transportation, Safe System Approach

https://www.flyingmag.com/garmin-autoland-flight-tested/

https://pavecampaign.org/canada/

Insurance Institute for Highway Safety

AVs and Disabilities: www.ncd.gov/publications/2015/self-driving-cars-mapping-access-technology-revolution